Shortlisted for the 2025 Republic of Consciousness Prize, UK & Ireland, for small presses

Longlisted for the 2025 International Booker Prize

They were driven by a single abject certainty: the best way to bring up children was to shut them up by terrorizing them! Rather than explain things, they petrified them, and they never resorted to persuasion because it was easier to intimidate.

Mes parents étaient animés d'une seule et abjecte conviction : que la meilleure façon d'élever des enfants était de leur clouer le bec en les terrorisant ! Ils n'expliquaient donc pas, ils épouvantaient. Ils ne persuadaient jamais puisqu'il était plus simple d'intimider.

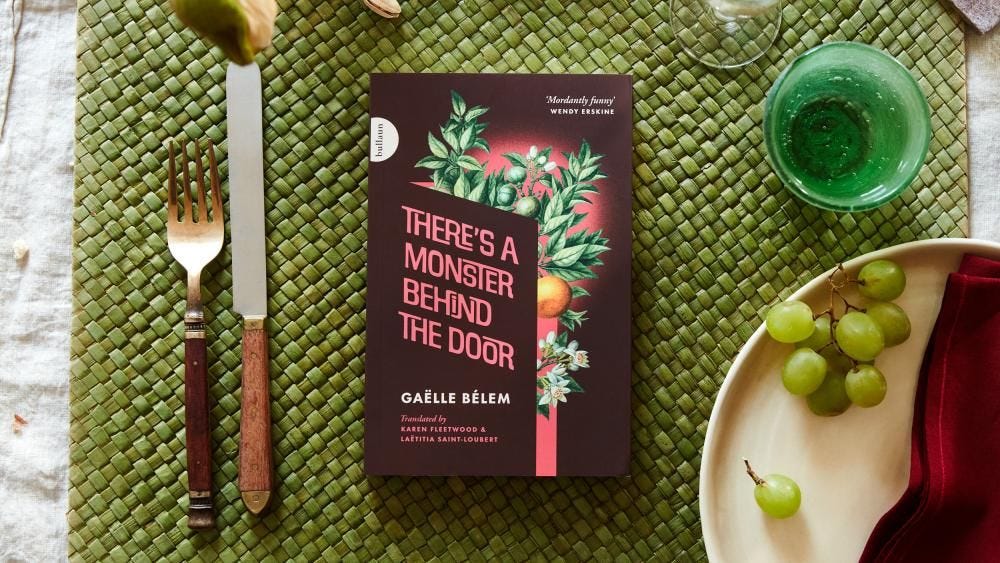

There's a Monster Behind the Door (2024) is the translation by Laëtitia Saint-Loubert and Karen Fleetwood of Gaëlle Bélem's debut novel Un monstre est là, derrière la porte (2020).

The novel begins:

‘That’s the way it is and that’s that!’

While parents usually get carried away trying to explain the great mysteries of life and the why and wherefore of everything to their offspring, the Dessaintes always proved exceptionally mean

when it came to explanations.

The translators and author of the novel prove rather more generous, with a useful foreword as well as 31 unobtrustive footnotes (some from the original, some added) as well as some helpful glosses.

The novel is set, starting in the early 1980s and covering c. two decades, on the island of La Réunion:

Welcome to the island of La Réunion in the 1980s: a heap of rubble on the edge of the world where the worst human superstitions, chased out by waves of European scepticism, had finally found a welcoming harbour.

[...]

Any anticolonialist from another French territory would have been quick to evoke the learned inferiority complex, traumatic memories, perverse determinism, collective neurosis and vicious circles of violence – but here they only talked of a difficult end to the century, of a century on its last legs. And it was then, as the sun set on this shipwreck century, that my parents took it into their heads to be born, to grow up, to get married and to perpetuate their line.

This humorous and disparaging tone is typical of the novel's narrator, a young woman, I think in her late teens at the time the novel is written, looking back on her life to that point. She is, with her mother, one of only two Dessaintes who hadn’t been locked up left in La Réunion, the Dessaintes an unruly family, and her parents taking little interest in her education, preferring superstition and scare-stories to science.

Indeed the narrator has a relationship with them, and her violent family, than reminds me of Matilda, although her own model is the 19th century author Jules Vallès (1832-1885), whose L’Enfant (The Child) he dedicated to ‘all those who died of boredom at school or were made to cry in the family, who, during their childhood, were tyrannised by their teachers or scolded by their parents’.

I read everything. Maupassant, Cicero, Hesse and Rostand, Süskind and Mirbeau. Loti, Melville, Seneca, Lautréamont, À rebours, Lao She and Livy. Anything that could be used as a door wedge or paper weight. Anything that would otherwise be easy fuel when we ran low on candles on the night of a cyclone. Lots of comics too. I would have sold my father for a Picsou Magazine or a Mickey Parade Géant. This universe of coloured speech-bubbles where the evil characters are not really that bad has never left me: the characters are just brainless individuals with clenched fists – a little narcissistic, a little complicated – who want to conquer the world out of sheer stupidity and boredom. So when nothing’s going right, when the walls get so high that even prayers can’t help you scale them, I open a comic book. As if leaning over a precipice, I dive right in, seeking a different world where no one can find me and I can forget. I have a book on my bedside table. Because I don’t have a gun.

This is a novel, in Saint-Loubert and Karen Fleetwood's vibrant translation of rich prose, steeped in the traditions of the island, although observed with an offbeat slant, this her imagining of her parent's wedding:

A few hours later comes the ordeal of the dessert: a wedding cake consisting of five tiers of choux puffs, decorated with arabesques, wafer flowers that have now wilted, and pink and blue ribbons. Just like the dole office, a long queue of half-asleep people forms, snakes its way towards the choux puffs and smacks two kisses on the cheeks of the bride and groom in exchange for a paper plate that contains a piece of the cake – a bizarre confection of liquorice syrup, soursop puree, preserved loquats, creamed red kuri squash, salted jackfruit and caramelized jujube. Nobody knows exactly what it is, only that it’s bad.

But under the humour, this is a powerful story of someone struggling to escape the trappings of post-colonialism, poverty and a troubled family legacy through learning and literature.

The judges' citation

“A rollicking, sardonic picaresque set on the French outpost of La Réunion in the. 1980s. The novel has important things to say about colonialism and society, but it’s also tremendous fun — darkly funny, acerbic, energetic. There’s scarcely a dull moment on the page, and the translation is remarkably slick.”

The press

A recent arrival on the Irish publishing scene, Bullaun Press has chosen literature in translation as its focus. It is the first such press of this kind in Ireland. We aspire to open up a space for readers seeking new and different voices.

Founder Bridget Farrell’s background in independent publishing and languages inspired her to set up Bullaun in 2021. She wants to see the press become an advocate for translators, especially Irish and Irish-based ones. Bullaun is open to approaches from translators looking for a home for a text that they are passionate about.

Translators will also be commissioned to work on recent books that could strike a chord with an Irish audience and beyond. As well as an enriching our reading experiences, it’s an important gesture of recognition of the cultural heritage of some of the many different language-speakers living in Ireland. We’d love to hear from you about compelling books that have not yet been translated into English.

What's a bullaun? (from Wikipedia)

A bullaun (Irish: bullán; from a word cognate with "bowl" and French bol) is the term used for the depression in a stone which is often water filled. Natural rounded boulders or pebbles may sit in the bullaun. The size of the bullaun is highly variable and these hemispherical cups hollowed out of a rock may come as singles or multiples with the same rock.

Local folklore often attaches religious or magical significance to bullaun stones, such as the belief that the rainwater collecting in a stone's hollow has healing properties. Ritual use of some bullaun stones continued well into the Christian period and many are found in association with early churches, such as the 'Deer' Stone at Glendalough, County Wicklow.

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/15419566.Paul_Fulcher